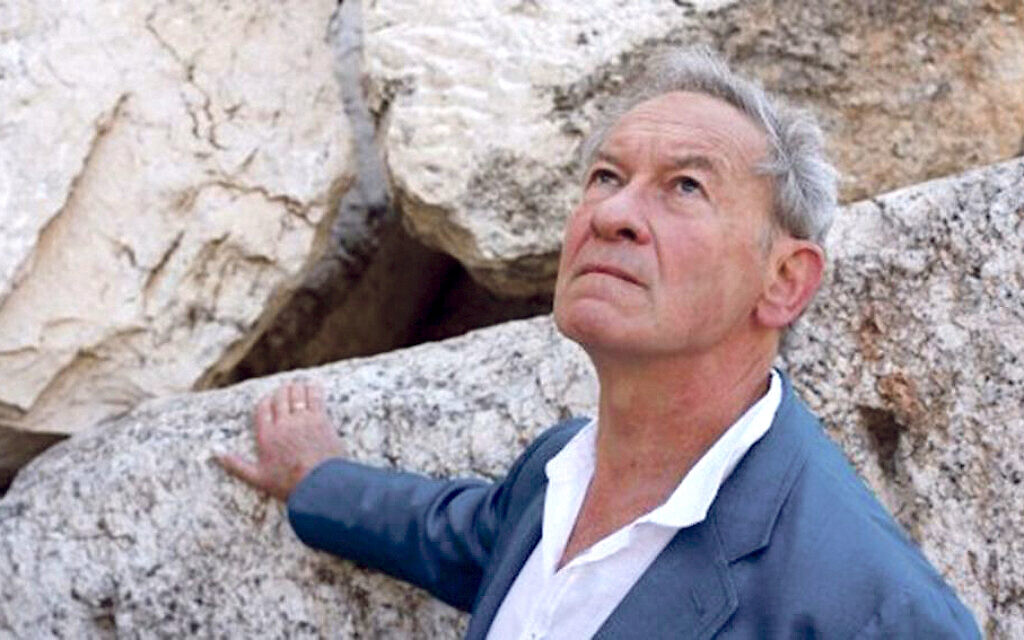

Simon Schama: How the Covid-19 virus caused antisemitism to go viral

In this extract from Viral Prejudice and the Jews, published in The Jewish Quarterly, the acclaimed author examines the relationship between antisemitism and scientific scepticism

In late July 2020, while Greece and Turkey were embroiled in a zero-sum battle for maritime spoils, a Greco-American was busy saving the world through his partnership with two German Turks.

The American pharmaceutical company Pfizer, in collaboration with the German company BioNTech, founded by the husband-and-wife scientific team Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, began the phase 3 clinical trials which would result, four months later, in the announcement of the first Covid-19 vaccine ready for manufacture and distribution.

Pfizer’s CEO is Albert Bourla, born and educated in the Thracian metropolis of Thessaloniki (erstwhile Salonica), while his two Turkish collaborators both come from families who immigrated to Germany.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Uğur Şahin was born in the western Anatolian town of Iskenderun (Byzantine Alexandretta), moving to Cologne in 1969 at the age of four when his father became a Gastarbeiter at the Ford factory in that city.

Özlem Türeci was born in Lastrup in industrial Lower Saxony, where her father was a surgeon in a local hospital.

Both their family histories, not to mention their research partnership, run spectacularly counter to the populist anti-immigrant rhetoric that has driven hard-right nationalism in Germany for the last decade.

While not making a great show of the fact, Bourla and his two Turkish partners have been content to allow their transnational collaboration to establish its own exemplary significance for an inescapably interconnected world.

Şahin has observed that the three of them “bonded over their shared background as scientists and immigrants”.

Bourla’s scientific education took place literally over the remains of his people

You would assume, then, that a partnership across historically adversarial national frontiers, a collaboration based on the universal imperatives of science, would deal a blow to nationalist intransigence and ancient demons. But modern times being what they are, you would of course be mistaken.

Retro politics persists, obstinately and angrily facing backwards even as the oncoming fury of the future – waves of viral pandemics, catastrophic degradation of sustainable ecosystems – slams into conventional norms of growth-driven power.

There is another fact about some of the leading scientist-entrepreneurs responsible for developing and delivering RNA messenger vaccines with a speed and urgency hitherto thought inconceivable, a fact that has not escaped the attention of the preternaturally suspicious: many of the most prominent among them are Jewish.

The chief medical officer of Moderna is Tal Zaks, an Israeli living in the United States; the chief scientific officer of Pfizer, Mikael Dolsten, is a Swedish Jew – his father a two-generation resident of Halmstad, his mother an Austrian Jew who escaped the Shoah.

Dolsten spent a year at the Weizmann Institute while working on his Lund University doctoral research.

Albert Bourla, who, like Dolsten, lives in New York state, is by origin a Greek Sephardi Jew from one of the few Jewish families to survive the Salonica Holocaust that, as Leon Saltiel writes, took the lives of 95 per cent of the 56,000 Jews living in that ancient city of Jewish settlement.

Bourla’s scientific education took place literally over the remains of his people, for Aristotle University, where he studied, was constructed on the site of a centuries-old Jewish cemetery, the largest in Europe, which, before its desecration and destruction, held the graves of some 350,000 Salonica Jews.

The final demolition of the cemetery occurred in December 1942 during the Nazi occupation, but the campaign to expropriate it for the benefit of the university had begun in earnest in 1936, five years after a pogrom in the Campbell district of the city.

A leading newspaper, Makedonia, and a philosophy professor at the university, Avrotelis Eleftheropoulos, dismissed any criticisms as obscurantist pseudo-religious objections to the necessary expansion of Hellenic civilisation.

A committee to defend the cemetery did what it could but in 1938 a portion containing 562 tombs and the remains of an estimated thousand, including some dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, were disinterred and removed to a new distant site, while a special Kaddish was recited on a day of mourning.

Further bites out of the cemetery were taken in 1939, so that although the German occupiers licensed the final destruction, its work had been long prepared by a Greek nationalist campaign. Marble was freely looted and, as Devin Naar’s Jewish Salonica notes, used, inter alia, for road construction, sea-walls, lining of latrines, repair of a Greek Orthodox church, and construction of a yacht club and a Wehrmacht swimming pool.

The extermination of the vast majority of Salonica’s Jews was followed after the war by the expedient disappearance of historical memory. Though there had been some evasion and resistance on the part of some Athenians, what took place in Salonica was notable for the absence of opposition and, as in so much of Nazi-occupied Europe, the collaboration of the local community.

For some seventy years, there was no visible acknowledgement of what had taken place, until, in 2014, mayor Yiannis Boutaris pushed for a modest memorial on the university campus.

Even so, reading the inscription would lead one to believe that the annihilation had been the work of the Germans alone. Most recently there has been discussion of a Holocaust memorial and education centre at Thessaloniki, though its future is uncertain. And in the meantime, the little memorial site has been the target of repeated anti-Semitic desecration: painted vandalism in 2017; smashed headstones in 2018 and in late January 2019, just a few days before International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

The 2018 assault was only tangentially a response to Jewish history (though a direct response to the demonology of anti-Semitism). It was part of the protests against the Tsipras government’s agreement to allow its neighbour to preserve the contentious word in the new name of the Republic of North Macedonia.

Such an ignominious appropriation of the memory of Alexander the Great, it was said by extreme opponents, was the result of “Balkans and Jews” sitting in the Athens parliament (where there are, in fact, currently no Jewish members).

None of this, however, prevented Greek media and politicians celebrating Albert Bourla as a modern Greek hero when, in November 2020, Pfizer announced the astonishing success rate of its vaccine.

This chimed perfectly with Bourla’s own embrace of his Thessaloniki birth and upbringing and his willingness to advertise his identification with contemporary Greece. An instant love fest broke out from New York to Athens to Mainz, the headquarters of BioNTech.

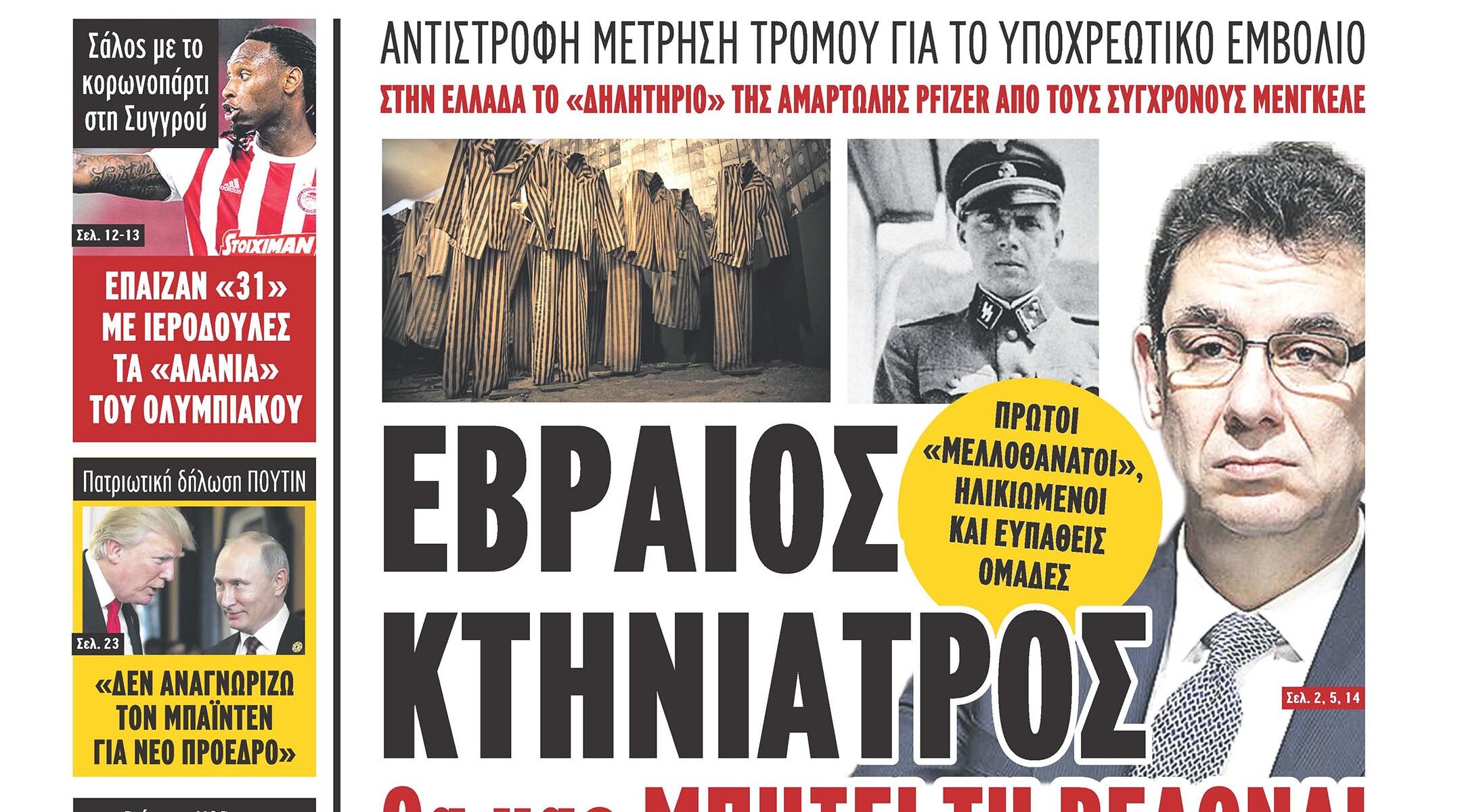

Except, however, for one newspaper, Makeleio, which broke ranks during the week of Pfizer’s announcement. Bourla, its front page screamed, was no hero but a Jewish veterinarian “about to stick a needle in us! Forced admission into concentration camps like herds!”

Just in case readers failed to grasp the point, a photo of Dr Mengele was printed alongside that of Bourla as comparable fiends of demonic experimentation. A few days later a second article accused Bourla, the “Greek Jew”, of “trousering millions for the ‘Israeli Council”’.

Makeleio is a publication of far-right fascist and neo-Nazi nationalists of the likes of Golden Dawn, with 8 per cent of Greek newspaper readership. Which is not to say it is without influence.

In the Anti-Defamation League’s most recent survey of attitudes towards Jews in European countries, Greece was reported as having one of the highest percentages of population endorsing the perennial items of the anti-Semitic repertoire: Jews wielding too much influence in the media, possessing too much money, dominating the globalised world and so on.

The paradoxical exploitation of Holocaust tropes and signs to refresh anti-Semitism – turning the victims of the Shoah into its new perpetrators – has been standard polemic in the more venomous zones of anti-Zionist diatribes.

Drawing on hoary tropes of the medieval blood libel, hated figures like Sharon and Netanyahu have been represented as shedding or even drinking the blood of murdered children.

The Covid-19 twist on these horrific lunacies is to equate the imposition of vaccines and even masks with a new Holocaust.

Anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers have taken to wearing yellow stars sewn on their coats; cartoons and signs have been published showing “victims” of compulsory social distancing and mask wearing being herded onto cattle trucks.

The jaw-dropping stupidity of equating the means of saving life with the historic insignia of mass murder in no way mitigates its obscenity. But then, logic and reason have no place in crowd paranoia, as evident from the mob invading the United States Capitol on January 6th wearing t-shirts bearing the logo “Camp Auschwitz” and “6MWE” (6 million weren’t enough).

Still more distressingly, a few Haredim have been guilty of the same misappropriation of Shoah memes to protest the enforcement of public health measures. The cry of “Nazi” is heard in Mea Shearim when mass gatherings are broken up or attempts are made to close shuls and yeshivot. Masks sewn with yellow stars have been seen in both New York and Israel.

The authority of knowledge has been under siege from those who march beneath the banner of pure belief

Was it idle to assume that, if from nothing other than collective self-preservation, the objective truths of science and the imperatives of public health derived from them might have constrained the most extreme assertions of populist paranoia and revelation-based religious conviction? Seen from America, it seems so.

For a long time now, the authority of knowledge along with the institutions created to further it – research laboratories, universities – have been under siege from those who march beneath the banner of pure belief. As Richard Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life argued long ago, much of American public culture, from the Puritan founding onwards, was grounded in revelation as well as in the uncontested authority of scripture.

It’s no accident, then, that the unhinged eschatology of QAnon named the date of the inauguration, 20 January, as the day on which the conspiracy of a deep-state, cabal-managed establishment of paedophile Satanists would be exposed and punished, and dubbed it “The Great Awakening”.

The original Great Awakening – the revival of evangelical preaching in the eighteenth century, has flowed copiously into the bloodstream of popular American convictions. Jefferson’s deism and his belief, embodied in his draft for the stature of religious freedom in Virginia, that religion and state power needed to be separated, won the battle of the First Amendment but not perhaps the war.

In fact, the freedom from religious legislation embodied in that amendment has recently been stood on its head in conservative judicial discourse to mean the rights of the religious to exempt themselves from civic obligations, such as accommodating guests or customers regardless of sexual orientation, for example.

But Jefferson’s commitment to the separation of state and religion always had to contend with the staying power of popular cults of revelation, messianism and millenarian End Times.

Historians have perhaps been too complacently Whiggish in assuming the inevitable fading of miracle politics in modern times. The 1925 Butler Act prohibiting the teaching of evolution was not repealed by the Tennessee legislature until 1967, but the classroom battle for Darwin has still not been conclusively won in states where evolution must compete with creationism and intelligent design as if it were just another theory.

Nor has the science of the pandemic scotched populism’s appetite for conspiracy theories, and still less has it resolved the great American epistemological crisis of the reception of knowledge. If anything, it has deepened it.

Myths about the origins of the virus almost immediately followed its first appearance. Helped by initial Chinese lack of transparency, Donald Trump’s labelling of the “China Virus” (repeated to the bitter end of his presidency) was always meant to imply that the whole thing was a plot cooked up in a state laboratory to sabotage his re-election and wreak havoc on the American economy, which under his stewardship had struck back against Chinese domination.

Crazier origin myths swiftly followed. The novel coronavirus was a fiendish invention of Bill Gates, and the vaccination was a pretext to implant 5G chips in the bodies of millions who would become enslaved to Microsoft and its Master.

And, inevitably, the virus was ascribed to George Soros, who became yet again the arch-demon of an international (read: Jewish) cabal running both deep state and paedophile Command and Control.

Lest anyone imagine these assertions were the stock of a tiny lunatic fringe, it has been estimated that QAnon has a following of tens if not hundreds of thousands in the United States alone.

Twenty Congressional candidates in recent elections endorsed this conspiracy theory, two of whom – Lauren Boebert of Colorado and Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia – were elected and show no sign of repenting or moderating those extreme views. Greene has expressly said that being called an anti-Semite will not deter her from attacking George Soros as the source of contemporary wickedness.

It did not help that the former president was a habitual “They-Sayist” – as in “they say” or “people say” whichever fantasy, unsupported by a scintilla of evidence, might help his re-election.

Thus “they say” hydroxychloroquine might be the miracle virus-stopper; “they say” injected bleach might do a terrific disinfecting job; “they say” that in warmer weather Covid will be gone, and so on – all aimed at minimising the Covid threat, even when records of telephone conversations show Trump understood its magnitude. The daily authorisation of fantasy and falsehood allowed into mainstream public opinion every kind of conspiratorial explanation of how the plague arose and how it kept its tenacious grip.

For as Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule pointed out in a fine paper in 2008, the persuasiveness of conspiracy theories owes much to providing wraparound, ostensibly coherent explanations for phenomena that otherwise might be seen as the unsettling product of chance and contingency – the forces which so often actually determine the course of history.

Once the virus had been established as the instrument of a malevolent plot, set in action by hidden actors, it followed that calls for mask wearing and the restriction of free movement would be construed as a conspiracy against personal and religious freedoms.

The right to go unmasked in indoor spaces like supermarkets, often militantly and sometimes violently asserted, as well as the right to gather in large numbers at Trump rallies or places of worship, became demonstrations of imagined constitutionally protected liberties.

When the science of public health was invoked to promote or enforce those constraints, this too was seen as part of a wicked mission bent on depriving religious believers and libertarians of God-given rights to do whatsoever they wished with their bodies, notwithstanding that much the same could be said of obeying seatbelt instructions on airplanes or stopping at red traffic lights.

From there, it was but a small step to regarding the entire phenomenon of Covid-19 as a “hoax” (as Trump once called it) or a calculated design to strip Americans of the fundamental liberties which made them American.

Disregarding the science or representing it as an elitist-globalist design on freedom became a patriotic calling if not an actual obligation. Likewise, vaccines could be seen as an instrument of alien invasiveness, a mass poisoning purporting to be a salutary prophylactic.

Jews could be mistrusted as being carriers of sickness and the monopolists of medical wisdom

It is predictable, then, to find those arch-cosmopolitan people, the Jews, featuring in the suspicions and conspiracy theories that hold both the virus itself and vaccination programmes as insidious.

Not all anti-vaxxers are anti-Semites, but the latest wave of fanatical populism engendered by a reaction against lockdowns and curfews includes anti-Semitic illiberalism in its repertoire. The demonisation of Jews as, simultaneously, adepts of esoteric medical knowledge and vectors of disease goes back to the very earliest expressions of Judeophobia.

In the second century, the Egyptian-chronicler priest Manetho rewrote the Exodus scripture, replacing a liberation saga with a history that had the Hebrews expelled from Egypt as carriers of leprosy.

The fiction had enough influence in the classical world for Josephus to mount a sustained contradiction in his own impassioned defence of Judaism, Contra Apionem. Just as Jews could be hated by anti-Semites as being both too poor and too rich, so they could be mistrusted as being carriers of sickness (the typhus and cholera libel attached to Jewish immigrants in late-nineteenth-century America) and the monopolists of medical wisdom.

In medieval and early modern Islamic and Christian states, Jews rose to prominence as court physicians and were suspected and feared for that very reason. During the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent there were twice as many Jewish doctors as Muslim at Topkapi Palace, so many that a separate guild had to be organised for them.

Their religion as well as the fame of their medical learning absolved them from fears that, unlike Muslims, they might be in the pay of dangerous rivals, or, like Christian physicians, have a score to settle. But being an outsider ministering to the most inside aspect of a ruler’s welfare always came with perils.

In England, the Marrano physician to Queen Elizabeth I, Roderigo Lopez, was accused of abusing his position on behalf of Spanish masters to poison the queen. Lopez had confessed under torture but recanted shortly afterwards, protesting his innocence. Though the queen herself seemed to doubt his guilt, her prosecutor, Sir Edward Coke, called Lopez “a perjured, murdering villain … a Jewish doctor, worse than Judas himself … not a Christian but a very Jew”.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Lopez was hanged, drawn and quartered in 1594 for the alleged offence, a satisfactory revenge for the ambitious Earl of Essex, whose treatment for venereal disease had been incautiously described by Lopez to the Portugese pretender in exile.

Jewish physicians were especially valued for their knowledge of antidotes to a wide range of venoms, which, in an age when poisoning was a habitual weapon of the politically motivated, made Jews simultaneously valuable and dangerous.

Many of those Jewish physicians had a deserved reputation for being scholars and rabbis as well as doctors; their deep, often multilingual learning and scientific expertise augmenting their skill at diagnosis and treatment.

But a reputation for being custodians of a storehouse of arcane wisdom could be turned against them individually and against Jews in general, most frighteningly during the manufactured “Doctors’ Plot” in the last year of Stalin’s dictatorship.

In January 1953, nine doctors, six of them Jewish, were arrested and accused of plotting to medically murder figures in the Soviet leadership. Stalin had prepared the way years earlier in 1949, by declaring that a “criminal underground” of Jews and Zionists were conspiring against the Soviet state and its leaders.

In 1953, Mikhoels’ cousin, Miron Vovsi, personal physician and therapist to Stalin himself, was among the arrested. When Nikita Khrushchev exposed the Doctors’ Plot to be pure fabrication following Stalin’s death, he also mentioned that the dictator had told him to urge workers in the factories of Ukraine to be issued with clubs so that they could “beat the hell out of the Jews”.

There is a body of opinion, based on statements by leaders like Nikolai Bulganin, that the plot was a prelude to a wholesale deportation to camps east of the Urals, probably in Siberia, to which Soviet Jews would be sent to “save them from the just wrath of the Soviet people”.

But suspicion of Jewish doctors and the clinical science of their vocation, coupled with a conviction that there are times when scientific knowledge should submit to some larger imperative – political or religious – is not a monopoly of non-Jews.

Far from laying those suspicions to rest in the name of collective welfare, the pandemic has widened the divide between communities of belief and communities of knowledge, to the point where the resistance of the former to the latter becomes abusive or even violent.

This in turn has raised fundamental questions about the authority of the secular state, in conditions of extreme crisis, to enforce science-based measures on communities where revelation-based beliefs are the ultimate arbiter of conduct.

Accustomed to praying indoors in considerable numbers, to packing students into Talmud Torahs and yeshivot, and because they often have large families living in modestly sized apartments, Haredi communities in the United States, Britain and Israel have been prolific incubators and transmitters of Covid-19, and some of the most truculently opposed to measures of containment and mitigation.

Demonstrations against mandated measures, especially social distancing and the closing of schools, have turned violent: members of the communities reporting on infringements denounced as “moysers” (informers); officials and police trying to enforce distancing and closures vocally denounced as “Nazis”; and, in one case in Brooklyn, Jacob Kornbluh, a reporter for a Jewish paper, severely beaten after being condemned by the Haredi-populist (yes, there is such a thing) radio shock-jock Heshy Tischler.

We are still stuck in an epistemological war between the multiplication of fantasy and the hard-earned truths of empirical inquiry

All this, of course, is merely the most extreme expression of a kulturkampf that has been raging in Israel, and in the Diaspora, over the kind of Jewish state it wishes to be; whether the secular democracy embodied in the original Declaration of Independence in 1948, which extended citizenship to persons of other religions, or whether the much narrower definition of Israel as an exclusively Jewish state, articulated in the nation-state law of 2018, is to prevail.

But even supposing that Judaism is now installed as the sovereign ethos of the state, the enormous question – especially in the Diaspora, where orthodoxy is neither the creed of the majority nor the defining condition of the religion – is what kind of Judaism is thereby established? And which variety of orthodoxy can claim ultimate authority?

That burning issue was raised nearly a millennium ago by the very paragon of the rabbinical physician, ministering not just to coreligionists but the world beyond Jews, and especially to its rulers: Moses Maimonides.

Inheriting from an impeccably rabbinical tradition the truism – pikuach nefesh – that the preservation of life overruled the strictures of Halacha – Maimonides’ teachings, not just on matters medical but on epistemological issues like differentiating between astronomy and astrology, which is to say between science and unsupported belief, the Rambam repeatedly insisted on the complementary relationship between philosophy and traditional Torah prescription.

Criticised for embracing and absorbing “Greek wisdom” – both Aristotelian and Neoplatonist – received via Arabic sources, Maimonides turned the accusation of hospitality towards pagan learning on its head by insisting that Judaism had rejected the credulousness of the “star-gazers” who imagined events and lives were affected by the constellations, replacing that coarse paganism with an uncaused divinity whose creative power was pure intellect.

None of this prevented The Guide for the Perplexed being seen as a gateway to free philosophical speculation and subjected to a ban by the French rabbis of Provence and Montpellier in 1232, twenty-eight years after the  Rambam’s death. His books were subsequently burned by the Dominicans in the same year.

Rambam’s death. His books were subsequently burned by the Dominicans in the same year.

It’s not that hard to imagine a present-day Maimonides substituting “posts” for “books” in his denunciation of “the fools who have composed thousands of books from emptiness and nothingness”.

In so many ways, we are still stuck in an epistemological war between the multiplication of fantasy and the hard-earned truths of empirical inquiry.

And whether in the realm of electoral politics, nationalist drum-beating or that of virology or climate science, these contentions are no longer, if ever they were, a mere matter of academic dispute.

Right now, and for the foreseeable future, the health of the world depends crucially on the victory of real, not imaginary, knowledge.

This is an edited extract of Simon Schama’s “Viral Prejudice and the Jews” in the relaunch issue of The Jewish Quarterly, The Return of History: New Populism, Old Hatreds, out now

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)