Without knowing the brutal history of this place, the sprawling mound rising from the earth just outside the town of Voranova, in Belarus, could easily be overlooked.

But for those who are all too aware, such as barrister and TV presenter Robert Rinder, it represents “the most articulate expression of human evil”.

For it was here that Rinder’s paternal grandfather’s family, having been deported from their homes in Lithuania, were forcibly marched by Nazi officers, told to lie down and murdered with machine guns.

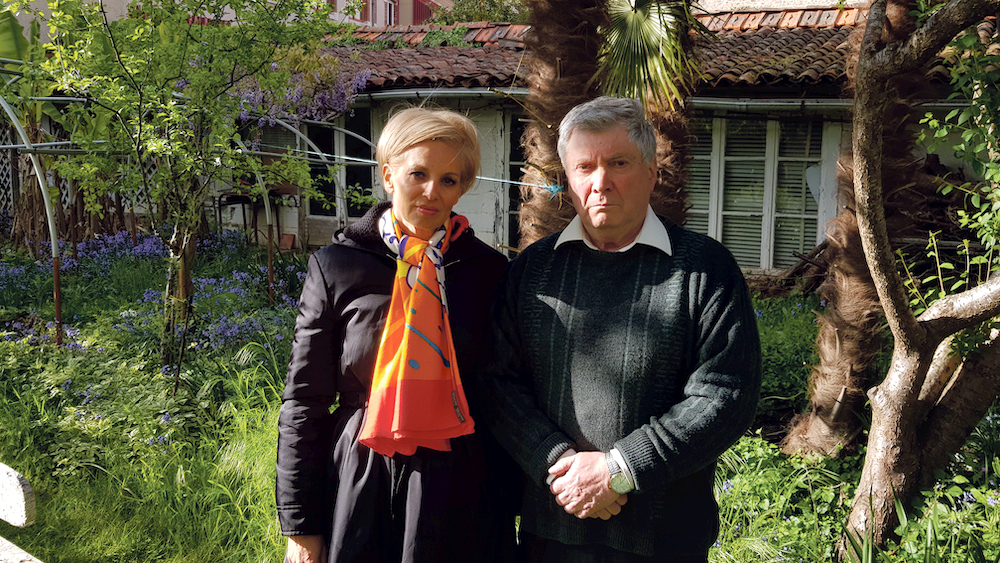

Remarkably, Rinder finds an elderly eyewitness to the horrific scenes that took place 80 years ago. It is just one of the many poignant scenes featuring in his new two-part series, My Family, The Holocaust And Me, which begins on BBC One on Monday, coinciding with the anniversary of Kristallnacht.

The documentary was inspired by Rinder’s moving story of his Holocaust survivor grandfather, which featured on Who Do You Think You Are? two years ago, as well as a desire to explore how such events have impacted second and third generation relatives like himself.

“What does it mean to be a second-generation survivor?” asks Rinder to explain why he wanted to make this series. “Who are our parents, who was I parented by and why do I feel insecure about the world in general?

“What you learn from the second-generation survivors, including my mother, Angela, is that they often share a number of emotional and psychological themes in their life despite not knowing each other.

“They have a deep sense of love, but also ambivalence for the damaged parents who went through such challenge, a profound loyalty laced in all sorts of complexity.

“Some people have an epiphany in life, where they manage to have a moment and locate their parents as a human being, but many of us don’t think about the experiences that led them to be the person they are and consequently the parents they became.”

While tracing what happened to Rinder’s relatives on both sides of his family, the series also follows the stories of three other families affected by the Holocaust.

Psychologist Bernie Graham travels to Germany for the first time to discover how his grandfather ended up with a life-changing injury, as well as the fate of his namesake, his uncle Bernhard, who was sent to Dachau.

Noemie Lopian makes a trip to France, where she has an emotional reunion with Jacques Deserces, the grandson of a man who hid her mother and her mother’s siblings in a chicken shed during Nazi raids, and learns how the young children embarked on a risky journey across the border to

Switzerland.

Meanwhile, cellist Natalie Clein and her actress sister Louisa, journey to the Netherlands to discover more about their grandmother’s incredible activities in the Dutch resistance.

All these stories were chosen specifically because they begin not in the concentration camps of Eastern Europe, but rather in Western Europe or, as Rinder explains, “places that had the outward veneer of enlightenment and democracy”.

He adds: “We wanted to show how in the right historical conditions – a socio-economic catastrophe and a treaty that people feel aggrieved by – the wrong person at the right time can come along and it takes almost nothing for a nation of laws to descend into the Shoah.”

The documentary also highlights how years of silence about the Holocaust has affected second and third generation survivors.

For Graham, the overriding feeling in his family was that he was “born into a state of bereavement”, something Rinder also understands.

“My mother would tell you she has the same echo in her life,” he tells me. “Her earliest memories were of quiet whispers about families and parents who weren’t there anymore, who had been killed and murdered. Nicht in front of the kinder, she would hear.

“It’s not so much that they didn’t say anything, but rather that they didn’t say anything for a long time. The whole world was in trauma, and so they didn’t think people wanted to hear.

“Secondly, they have to find emotional strategies to rebuild their lives. Just think of the magnitude, of having to sit down and say my four sisters, my brother, my parents were all murdered. No wonder they didn’t speak until later in life.”

Yet for all the trauma and tragedy these survivors endured, Rinder was heartened that many of the stories emerging are ones of hope.

In one particularly emotional scene, Rinder and his mother meet 92-year-old Leon Rytz, the last survivor of Treblinka who, despite seeing his entire family murdered there, went on to rebuild his life after the war.

“It’s almost universally true that the narrative of the survivors I’ve had the gift of experience from, have all made this conscious choice to curate their lives in light and optimism. They found joy despite having experienced a trauma most humans can’t imagine.”

He adds: “Almost every story was overwhelming and yet there was this feeling of optimism. It’s not what I anticipated, but emerged like a light out of the darkness.”

My Family, The Holocaust And Me starts on Monday, 9 November at 9pm on BBC One