Oslo Accords at 25: Peace in pieces

It was supposed to signal an end to enmity but, 25 years on, Oslo was perhaps the greatest missed opportunity for peace

On 13 September 1993 a ceremony took place on the White House lawn. It marked the signing of the Oslo Accords, the hitherto unprecedented process which laid the groundwork for peace between Israel and the Palestinians.

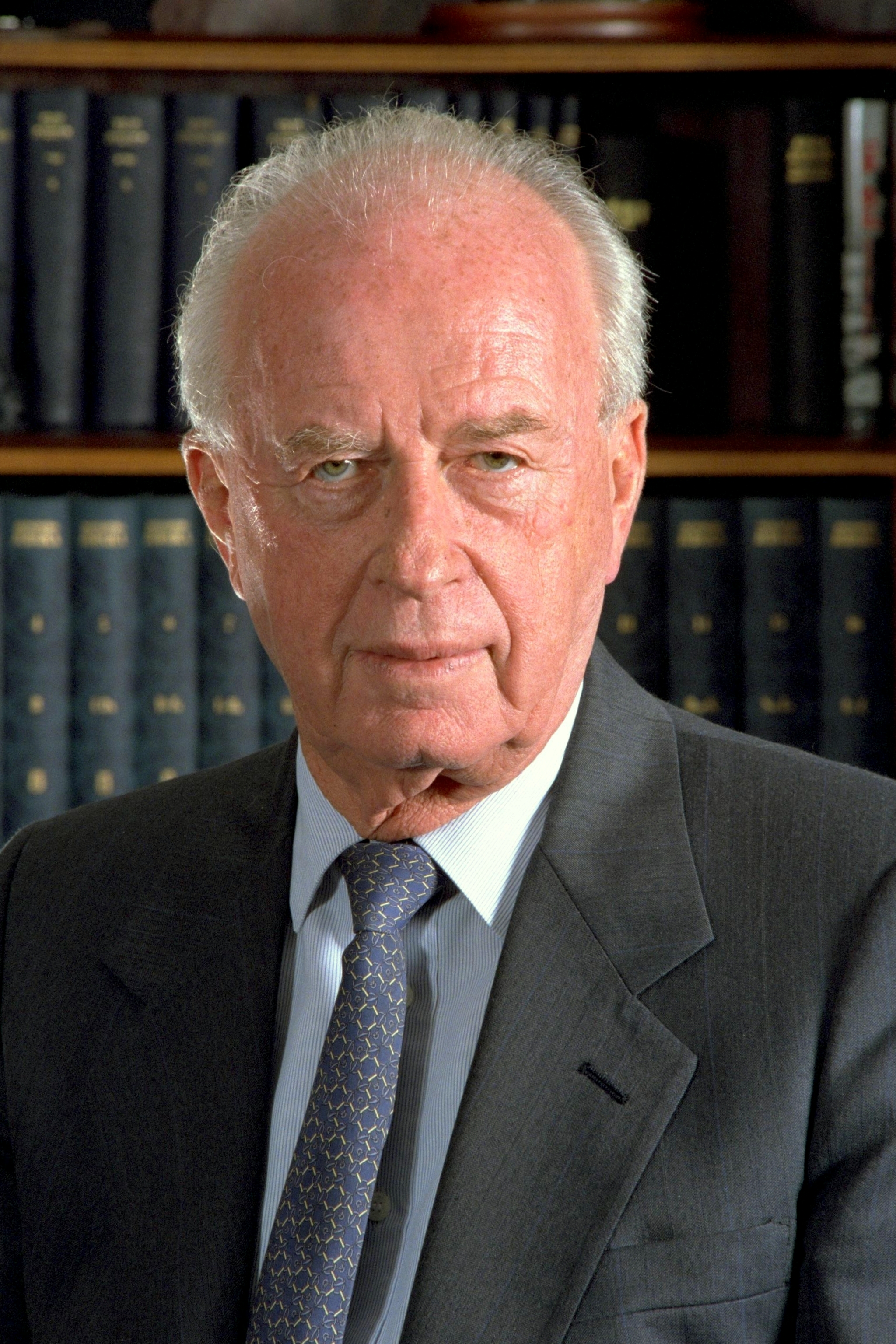

Three of the protagonists on that extraordinary day – Yasser Arafat, Yitzchak Rabin, and Shimon Peres – are now dead. Only former President Bill Clinton, who oversaw the signing like a proud new father, still has memories of what it took to get from Oslo to Washington.

It’s almost impossible now to remember the optimism of Oslo, the hopes the Accords raised in Israelis — and, to a lesser extent, in Palestinians. There was a definite feeling that peace was round the corner. If Yitzchak Rabin, “Mr Security”, could overcome his palpable distaste, and shake Arafat’s hand, anything could happen.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

And, of course, these early hopes and prayers went largely unrealised. But although popular myth — particularly on the right-wing of Israeli politics — has declared Oslo “dead in the water” — there are still people who were involved in the back-channel negotiations who have important observations about the Oslo Accords — both historically and as a building block for future negotiations.

Some of them have spoken at length to Fathom, the in-house journal of Bicom, the Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre.

Hussein Agha was an adviser to both Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas, today’s Palestinian president. He is not himself Palestinian, but grew up in Lebanon and joined Arafat’s Fatah faction, swiftly becoming part of Arafat’s inner circle.

Agha’s view, he tells Fathom editor Alan Johnson, is that Oslo was an attempt by Israel to resolve its security predicament, not a historical resolution of the conflict. Today, he says that Israelis and Palestinians have to get to grips with their conflicting narratives and try and reconcile them through some kind of truth and reconciliation commission — and urges a public process which goes beyond elite level negotiations.

Describing Oslo as a “straitjacket”, Agha says both sides need to look for something new. And part of that is his conclusion that the United States “never appreciated the psychology of the parties or how to address their deep fears and dark hesitations”. For Hussein Agha, the only way forward is for Israelis and Palestinians to talk directly to each other, specifically proposing that refugees and settlers must be involved directly. He says: “You have to hear their voices” as they are the heart of the conflict.

Unlike Agha, the Vienna-born Yair Hirschfeld, a professor at Haifa University, still sees things to take from Oslo. Hirschfeld and the late Ron Pundak were the two Israeli academics who first began negotiations with the Palestinian team, even while it was still illegal for Israelis to meet PLO members face-to-face.

Credit: Arnie Sachs / CNP

From at least one point of view, Hirschfeld says, “Oslo failed”. And that is, he says, in terms of PR, which was “a total disaster” insofar as the “public knowledge that Oslo was a complete failure”.

He says: “Oslo never promised a rose garden. And the big mistake of Peres and Rabin was to say that Oslo was a peace agreement, which it never was. Rather, it was a set of principles to work together on a peace-building process”.

Rather than simply write off Oslo as a failure, Hirschfeld thinks it contains elements of success, and his recommendation is that both sides should use it as a basis for advancing peace-making today.

He acknowledges that the situation is “schizophrenic” because “on the ground, there is very good co-operation”. Hirschfeld’s approach is a gradualist one. He talks about “five pillars” in the Oslo Accords: “upgrading and stabilising Israel’s alliance relationship with the United States on a long-term bipartisan basis; preventing further deterioration between Israel and Europe; stabilising and improving the extreme volatile relationship between Israel and our Arab neighbours; overcoming the internal divide within Israel; and developing a functioning partnership with the Palestinian people”.

On the “third pillar”, improving Israel’s relationship with the Arab world, Professor Hirschfeld is fairly optimistic. He says: “Long-term strategic understandings with the Arab and Muslim world are vital for Israel. And there is now an opportunity for this. The political leadership in Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, as well as in the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and elsewhere is reaching out to us. They both need and want an accommodation with Israel, but a stable alliance cannot be achieved independently of an agreement with the Palestinians”.

And he warns of a potential deterioration in relations with Europe, and the spread of “Corbynism, particularly if Corbyn becomes British prime minister”.

Hussein Agha was not initially directly involved in the Oslo process. He tells Fathom: “I was aware of something happening away from Washington, but I was not aware of Oslo and did not know the people involved. I had nothing to do with it. Once I knew, my initial reaction was to be against Oslo.

“For me, the main Palestinian problem and the core of the conflict were the refugees. I was shocked that Oslo did not address that: ‘How could this be a step toward a solution when it doesn’t deal with the core issue?’ I met the Foreign Minister of Norway, Johan Holst, in Oslo and I told him my feelings. He looked tired, said he agreed, but that we had to start somewhere. He died a few weeks later.

“It was around then that I really met Abu Mazen (Mahmoud Abbas, today’s Palestinian president). My colleague Ahmed Khalidi and I were tasked to start talks with the original Oslo team, to come up with a final-status agreement. This became known as the Stockholm track.

“I remember that half-way through I wanted to quit the talks, thinking my Israeli counterparts were not as well connected on their side as I was on mine. But Arafat and Abu Mazen disagreed. I remember sitting with Arafat in his bedroom at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm when he was visiting and he burst out, ‘Do you think I’m stupid? Do you think Yossi Beilin [the then Israeli Minister of Justice] would be doing this without Prime Minister Rabin knowing about it?’ I said: ‘Beilin claims Rabin doesn’t know anything about it.’ Arafat replied: ‘Of course he would say this. And if anyone asked me if I knew you, I would say that I didn’t.’ Point taken”.

The agreed “Stockholm” document, Agha recalls, was given to Shimon Peres after Rabin’s assassination in November 1995. “Peres didn’t have time for it,” says Agha. “He wanted to concentrate on the Syrian track and winning the general election in Israel. As it happened, he didn’t win the election. His opponents used the slogan ‘Peres will divide Jerusalem.’

After the elections, Dore Gold [the Israeli diplomat who was then Israel’s envoy to the Palestinians] told Agha that if that document had been made public before the elections, Peres might not have lost, because it would have been clear that nothing in the document suggested dividing Jerusalem. Instead, it said that the city was to be a joint capital of both states, united in all aspects except there would be separate authorities in the Arab and in the Jewish neighbourhoods”.

Looking back, says Agha, “I have concluded that Oslo was more than anything else an attempt by Israel to resolve its security predicament by making the Palestinians responsible for Israel’s security in the territories — and saving Israeli money allocated for basic services in these areas.

“There were some Israelis around the Oslo process who really did want a Palestinian state, but I think for the majority of mainstream Israelis it was not about ending the conflict, but about defusing the violence that they feared the first intifada would develop into and saving resources spent to upkeep Palestinian society in the West Bank and Gaza.

“I believe the Palestinians entered Oslo with good intentions, hoping for an independent, sovereign state. After the assassination of Rabin, Arafat felt that was no longer going to happen. When news of Rabin’s death reached Arafat, he was with a close confidante. He was silent for a long time and then he told his friend, ‘This evening they did not only kill Rabin, they killed me as well.’ Arafat knew it was the beginning of the end for Oslo, and for himself. He was right”.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

- Oslo Accords

- Oslo

- yasser arafat

- shimon peres

- Yitzchak Rabin

- President Bill Clinton

- Washington

- Fathom journal

- Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre

- Hussein Agha

- Yair Hirschfeld

- Ron Pundak

- Foreign Minister of Norway

- Johan Holst

- Features

- News

- Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas

- Britain Israel Communications and Research Centre (BICOM)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)