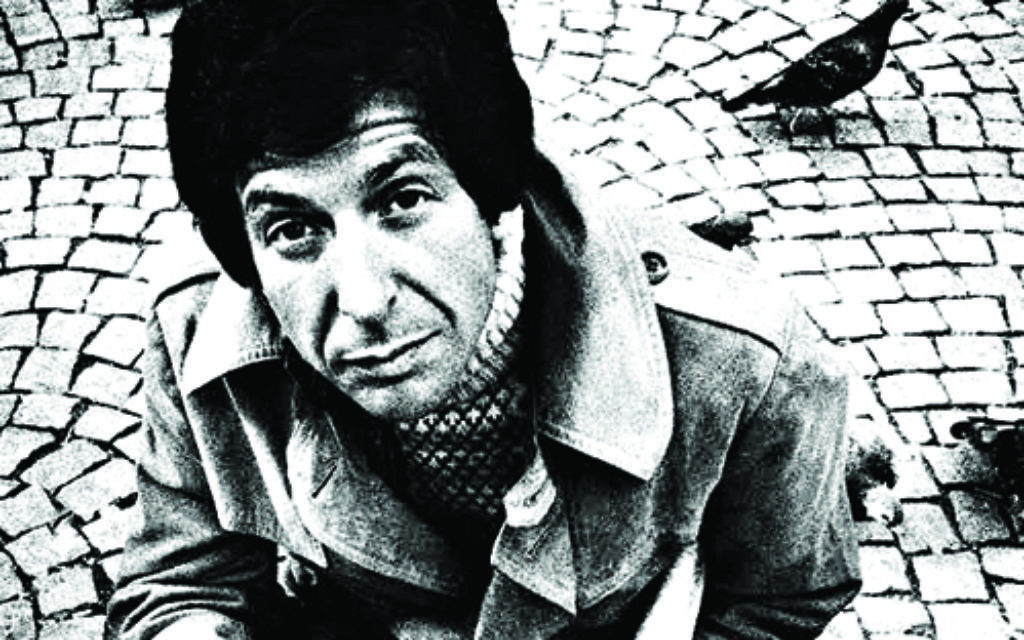

As Leonard Cohen turns 80, a new book examines his life and music

As Leonard Cohen turns 80 next month, author Liel Leibovitz takes a look at what has made the Canadian songwriter such an enduring cultural icon in his recently-released book, A Broken Hallelujah.

Revisiting the most pivotal moments in Cohen’s life, Leibovitz examines Cohen’s upbringing within an Orthodox Jewish family, his years spent as a recluse on the Greek island of Hydra, his devotion to Buddhist philosophy and, of course, the melancholy yet impassioned music that has made him popular with audiences spanning generations.

In this compelling extract, Leibovitz takes a look at the influence of Bob Dylan in persuading Cohen to take up a career as a musician:

“Leonard Cohen’s decision to abandon his modestly successful career as a writer and a poet, at the age of 32, in order to become a singer, is so profoundly strange that attempts to explain it tend to be either banal or fantastic.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

On the one hand, some of Cohen’s biographers have suggested that he picked up a guitar when he realised that entertainers were far more handsomely compensated than poets.

It’s a plausible premise, but it leaves Cohen in the position of being clueless enough to believe that, as an older man – Elvis, born a few months after Cohen, had already become a star and served in the army and made terrible movies and retired from show business by the time Cohen first announced his musical aspirations – with a nasal voice he could simply march down to Manhattan and become a singing sensation.

Cohen was always audacious about his career, but he was never naive; money might have played a part in his decision, but it was very likely not the only, or even the central, one.

What made him sing? As is the case with all seminal moments in his life, Cohen, when asked, had a fanciful explanation at the ready…

Sometime in 1965 Cohen discovered the young Jewish poet, nearly a decade his junior, and was immensely drawn to Dylan’s cryptic, haunting lyrics. In his interview with Adrienne Clarkson, he took the time, apropos of nothing, to cite the line from Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man about fading into one’s own parade.

By the time he attended a drunken gathering of Canada’s poets, one week after New Year’s Day of 1966, Dylan was all he wanted to talk about… He left promising that he’d soon be the new Dylan. No one in the room believed him.

It’s not hard to see what may have attracted Cohen to Dylan. Like Cohen, Dylan grew up in a family that was actively involved with its local Jewish community, and with a grandfather who studied the Talmud each afternoon.

Both men, when young, attended Zionist summer camps – Cohen’s called Mishmar, Dylan’s Herzl – and were taken with the Jewish folk songs they learned there; in 1961, performing in Greenwich Village, Dylan parodied one such song, Hava Nagila, which he claimed jokingly was a strange chant he’d learned in Utah.

But, most important, Dylan was on fire. Listening to With God on Our Side or Masters Of War, it was easy enough to imagine that if Isaiah had been born in the 1940s, he’d’ve found his way to the stage at the Gaslight Cafe to sing and preach.

Listening to Dylan, Cohen heard the same language he’d heard years before, studying the prophets with his grandfather. Sometimes, the lines came directly from the scriptures: I and I, for example, a song from Dylan’s 1984 album Infidels and one of Cohen’s favourites, features the line “no man sees my face and lives”.

It was spoken once before, by God, in the book of Exodus. Dylan wasn’t just citing the ancient tradition; he was continuing it. He understood – by most accounts, subconsciously – something profound about the role prophecy played in Jewish life.

The rabbi and theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel described that role well: “In speaking about revelation,” he wrote, “the more descriptive the terms, the less adequate is the description. The words in which the prophets attempted to relate their experiences were not photographs but illustrations, not descriptions but songs.”

Even as Jews replaced their ecstatic modes of worship with other, more cerebral ones, they nevertheless kept singing their messianic songs.

In his study of Dylan’s Jewishness, Seth Rogovoy identified the singer as a modern-day badkhn, or joker, a traditional figure serving as “a pious merrymaker, a chanting moralist, a serious bard who sermonised while he entertained … the sensitive seismograph that faithfully recorded the reactions of the common man to the counsels of despair and to the messianic panaceas.”

Dylan tried to be a badkhn-as-poet – “I search the depths of my soul for an answer,” he declared in an early college poem, “But there is no answer / Because there is no question / And there is no time” – before realising that bards belonged onstage, walking into a coffee house called the Ten O’Clock Scholar, introducing himself not as Robert Zimmerman but as Bob Dylan, and securing his first gig.

By 1966 Leonard Cohen was heading in the same direction.

• A Broken Hallellujah: Leonard Cohen’s Secret Chord by Liel Leibovitz is published by Sandstone Press, priced £14.99. It is available now.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)