Drawing Inspiration from Ben Uri’s 100 for 100 exhibition

Jewish News visits the Ben Uri Gallery's exhibition, showcasing some of the most iconic Jewish artwork from the last century

Francine Wolfisz is the Features Editor for Jewish News.

Francine Wolfisz tours the Ben Uri Gallery’s 100 for 100 exhibition at Christie’s, showcasing some of the most iconic artwork by 20th century Jewish artists

What started as a small gathering at Gradel’s restaurant in Whitechapel quickly transformed into a mighty champion for Jewish art. Now 100 years on, the Ben Uri Gallery is celebrating its century-long story with a stunning exhibition opening this week at Christie’s South Kensington.

Spread over three rooms, 100 for 100: Ben Uri Past Present and Future presents a rare opportunity to enjoy a small portion of the 1,300-large collection owned by the St John’s Wood museum, which is largely kept hidden from public view.

The exhibition starts at the very beginning, with an intricate, circular design piece by founding artist Lazar Berson, which was created to mark the very first anniversary of the Jewish art society he had established. Despite its humble beginnings, with the help of fellow artist and jeweller Moshe Oved, the society had grown to more than 100 members by 1916.

As we continue through the exhibition, the walls are filled with the spectacular works of these founding members, which reflect on issues of family, Jewish traditions and migration. They include Solomon Hart, notable for becoming the first Jewish Royal Academician in 1840 and Solomon J Solomon, who after a nearly-70 year gap became the second and later on, president of Ben Uri.

Sarah MacDougall, Ben Uri’s head of collections, explains that few Jewish artists received membership to established societies like the Royal Academy during this era.

“There was no official rule as such, but this large gap certainly suggests something. That’s why a society like Ben Uri was very much needed to be specifically Jewish”.

Almost all of these early artworks show a tenderness, longing or return towards the respective artist’s Jewish identity. Samuel Hirszenberg’s Sabbath Rest (1894) is an evocative depiction of three generations poised to leave behind their lives in Lodz for other shores. Alfred Wolmark’s The Last Days of Rabbi Ben Ezra (1905), one of the exhibition’s “star attractions”, was completed by the artist after he travelled to Poland “to steep himself in the old ways”.

Simeon Solomon, a child prodigy who embraced Christianity in later life, thinks back to the traditions of his youth with The Rabbi (1893). His life ended somewhat tragically after he was prosecuted for homosexuality and spent his final days destitute in a workhouse. Despite his obvious talent, his work was supressed and Solomon was shunned by the art world – except for the Ben Uri society.

“That was a brave act, given that Solomon’s work was still supressed at that time. To champion him despite this shows a very strong commitment to art,” explains MacDougall.

The story behind Lily Delissa Joseph is equally intriguing. In her Self-Portrait with Candles (1906), the artist presents herself as an Orthodox Jewish woman, but she was also “a very radical character” and staunch suffragette – in fact she missed her own private view because she was imprisoned in Holloway at the time.

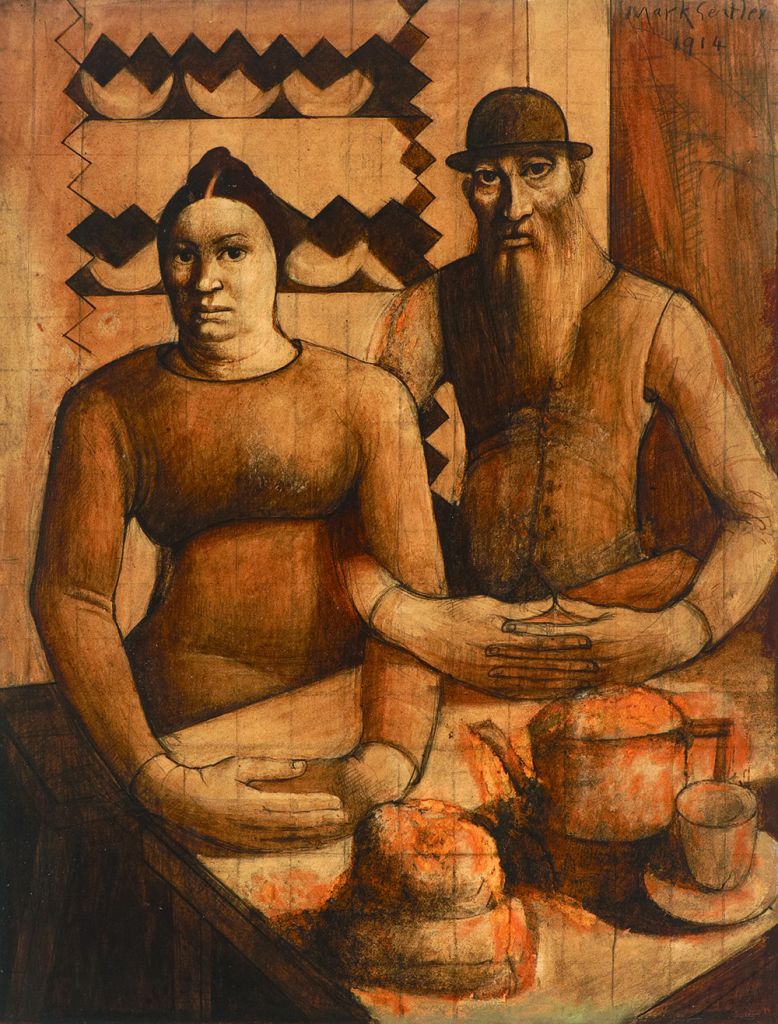

A section of the exhibition is dedicated to the so-called Jewish School of Paris, which includes Emmanuel Mané-Katz, Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall, Moise Kisling, Sonia Delaunay and Jacques Lipchitz, as well as the Whitechapel Boys, which includes Mark Gertler and David Bomberg among their number.

The latter has two works on display: Racehorses (1913), which shows his radical, forward-thinking talent with his chalk and wash drawing of horses that were called “a waste of good wall space and pigment” by critics; and Ghetto Theatre (1920), a much darker picture reflecting Bomberg’s state of mind after he witnessed the horrors of the First World War.

One of the most poignant exhibits on display is Isaac Rosenberg’s Self-Portrait in Steel Helmet (1916), created on brown paper while the young artist took cover in the trenches. Just two years after sending his portrait to his family, Rosenberg was killed in action.

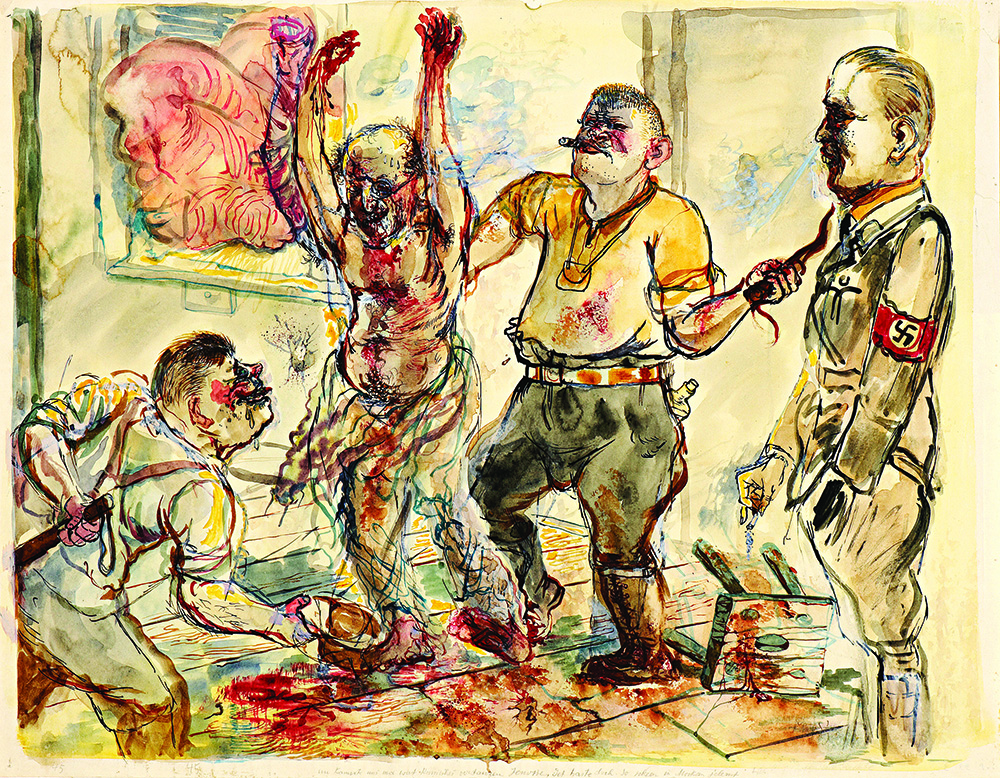

The horrors of the Second World War are equally reflected in works by the non-Jewish, “degenerative artist”, George Grosz, in his graphic Interrogation (1938), referencing the tortuous death of his Jewish friend, anarchist Erich Mühsam and Emmanuel Levy’s Crucifixion (1942), a personal protest against Jewish persecution in mainland Europe.

Similarly, Marc Chagall’s Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio (1945), uses the crucifixion of Christ as

a way of alluding to the Holocaust for the first time.

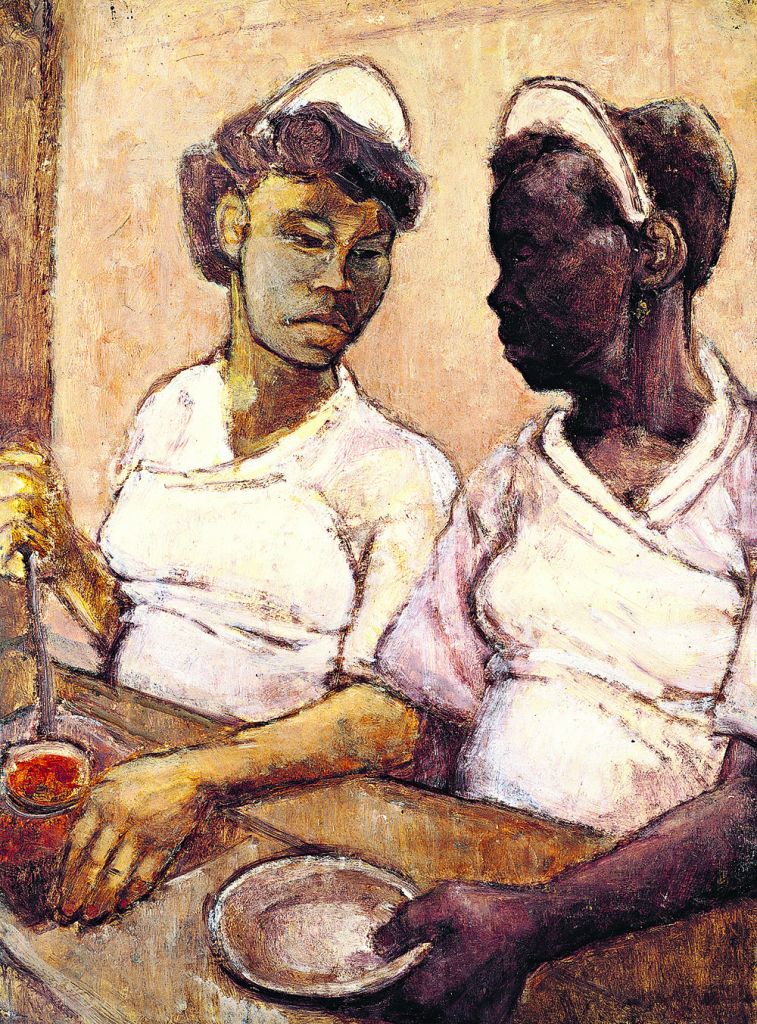

Moving into the post-war era, the exhibition changes pace with an eclectic mix of artwork from Hans Feibusch, Leon Kossoff, Frank Auerbach and Eva Frankfurter.

As 100 for 100 heads towards its conclusion, the displayed works reflect the change from Ben Uri’s original focus on specifically Jewish artists to a collection that now also includes the works of artists from around the world.

MacDougall concludes: “It’s a wonderful showcase not only of the collection and the importance of our Jewish history, but also the continuing themes of identity and migration in the art of today.”

• 100 for 100: Ben Uri Past Present and Future runs until 9 June at Christie’s South Kensington, Old Brompton Road. Details: www.christies.com/exhibitions

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

- Ben Uri

- Christie’s

- South Kensington

- St John’s Wood museum

- Lazar Berson

- Moshe Oved

- Jewish traditions

- migration

- Jewish Royal Academician

- Sarah MacDougall

- Lodz

- Rabbi Ben Ezra

- Simeon Solomon

- homosexuality

- Lily Delissa Joseph

- Orthodox Jewish women

- Emmanuel Mané-Katz

- Chaim Soutine

- marc chagall

- Moise Kisling

- Sonia Delaunay

- Jacques Lipchitz

- Mark Gertler

- David Bomberg

- ghetto

- Isaac Rosenberg

- art

- Arts

- Kosher Culture

- Culture & Lifestyle