A ‘secret listener’ reveals how he bugged the Nazis

This week marks 77 years since the beginning of the Second World War, we talk to 97-year-old Fritz Lustig, one of only two surviving ‘secret listeners’ who eavesdropped on German prisoners…

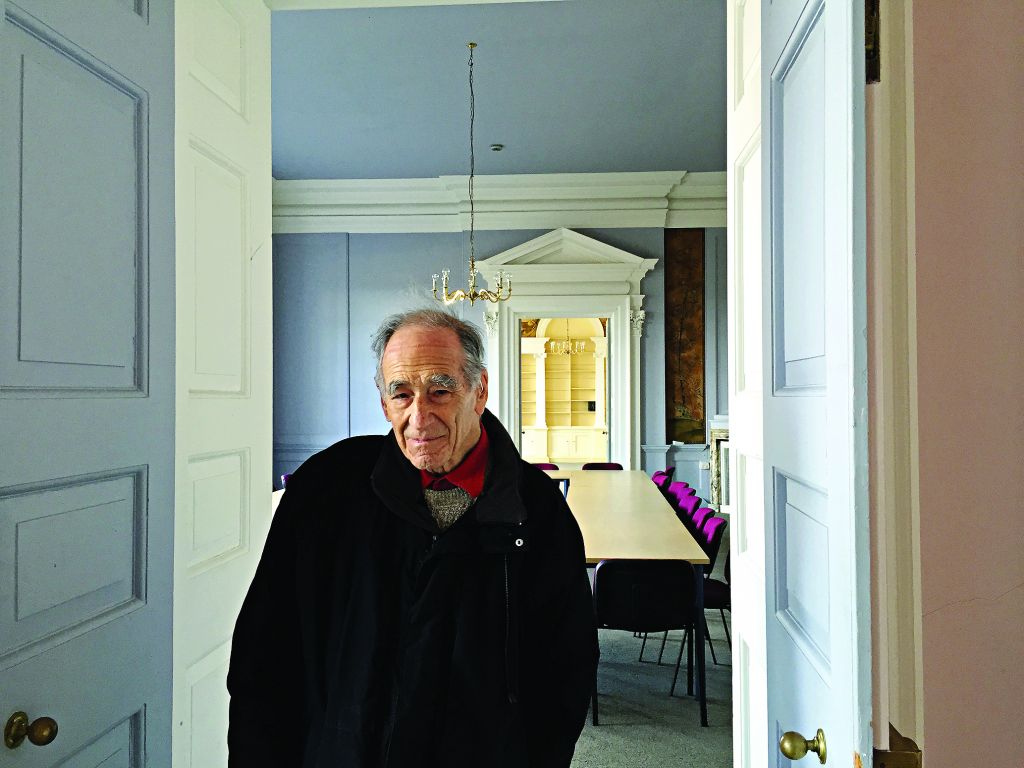

The often-quoted saying, “if walls could talk” has an untold poignancy for a man like Fritz Lustig. For the German-Jewish refugee, who was recruited to work for British Intelligence during the Second World War, the walls certainly did “talk” at Trent Park, Latimer House and Wilton Park, having been fitted with hidden microphones to record the conversations of more than 10,000 German prisoners.

Today, Lustig is one of just two surviving “secret listeners” who eavesdropped on admissions of war crimes and atrocities against Russians, Poles and Jews, details of an SS mutiny in a concentration camp in 1936, and Hitler’s human ‘stud farms’.

Their work remained classified until 1999, with many who helped to save the nation going to their graves still bearing the secret of their life-saving efforts. Fortunately, Lustig is more than happy to meet at his Muswell Hill home and speak about his intriguing wartime work.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

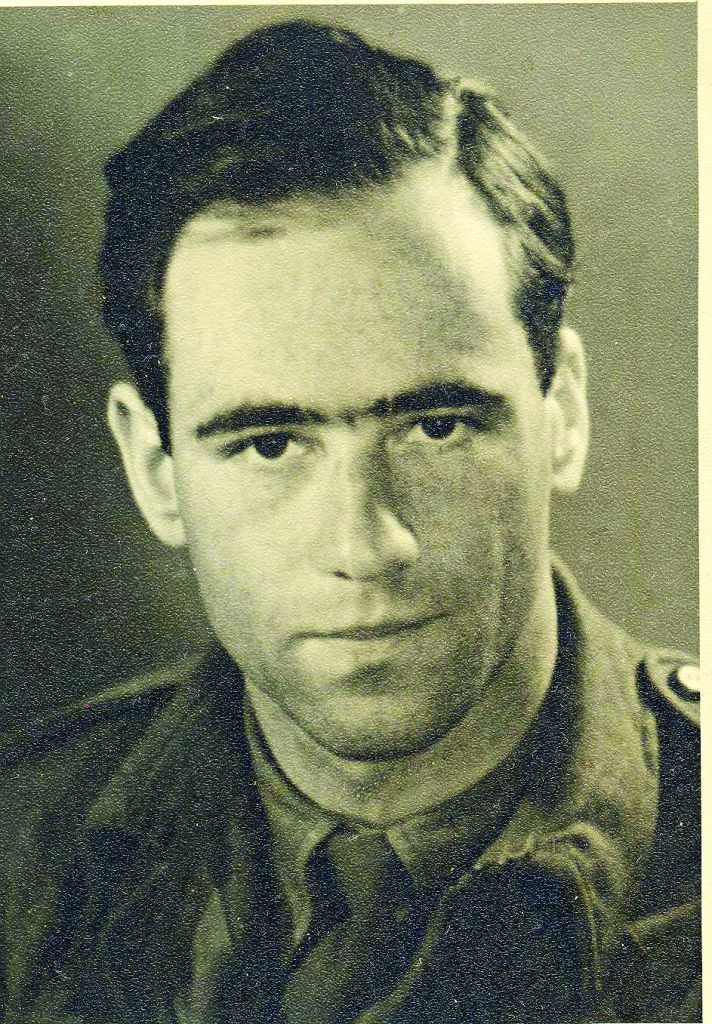

Now aged 97, the unassuming hero looks sprightly, with finely-chiseled features and a twinkle in his eye. Born in Berlin in 1919, he was conceived after his father returned from active service in the First World War and was the youngest of four siblings. His family included a prominent ancestor, Rabbi Ludwig Philipsson, who founded Germany’s first Jewish newspaper during the 19th century.

“Thankfully all my family managed to get out of Nazi Germany and survived the Holocaust,” Lustig tells me. After graduating from school, he was apprenticed to a Jewish company that produced dental equipment, but was dismissed following Kristallnacht. “It became obvious it was imperative to leave Germany as soon as possible,” he explains.

Lustig left for England in 1939 and was hosted by a family in Hertfordshire whom he had known previously. His eldest sister followed on a domestic permit and became housekeeper for a Cambridge professor.

Just a year later, Lustig faced further upheaval when, due to his German nationality, he was interned by the British as “an enemy alien” and sent to a camp on the Isle of Man, where he played the cello in concerts with other interned musicians.

Just a year later, Lustig faced further upheaval when, due to his German nationality, he was interned by the British as “an enemy alien” and sent to a camp on the Isle of Man, where he played the cello in concerts with other interned musicians.

After his release, he volunteered for the Pioneer Corps, the only regiment open to ex-German refugees. The intervention of a friend of his mother who worked for British Intelligence led to Lustig being recruited to the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre (CSDIC) to train as a secret listener. “We were told what information to listen out for and to pull levers to record whenever we heard anything of importance,” he recalls.

As a native German speaker, Lustig could pick up the nuances of what was being said. “We had to learn to distinguish between different voices and dialects. They paired two people with different pitches so that we could discriminate between their voices more easily.” The recordings were made on shellac discs and the secret listeners were ordered to stay on duty until the prisoners fell asleep – “some kept talking after lights out”, he explains.

In all his time as a secret listener, neither Lustig nor any of his colleagues actually met any of the Germans they spied on. They monitored their ex-countrymen at three prisons in country houses at Trent Park in north London and at Latimer House and Wilton Park, where Lustig was stationed, both in Buckinghamshire.

“Where I served at Latimer House and Wilton Park, the prisoners never stayed longer than a week – by that time it was assumed that they had spilled the beans or never would,” says Lustig wryly.

The most comfortable prison, Trent Park, was reserved for around 60 captured German generals, colonels and senior ranking officers. Despite protestations from Churchill, they were housed in spacious, high-ceilinged rooms to encourage them to relax and talk. The officers were permitted to stroll around the grounds – but unbeknown to them, the trees and bushes were bugged with sensitive microphones to pick up their conversations.

Did Lustig overhear anti-Semitic remarks during his eavesdropping?

“Some prisoners were die-hard Nazis and others wanted to help the allies although they pretended to be good Nazis,” he replies

When the prisoners talked about atrocities, the transcriptions were marked specially and kept in a permanent archive.

The transcripts of around 100,000 records are now declassified and kept in the National Archives at Kew. Historian and biographer Dr Helen Fry has researched thousands of these records for a series of books, including The M Room: Secret Listeners Who Bugged The Nazis.

I ask Lustig what is the most interesting thing he remembers overhearing.

“At first most of the prisoners I listened to were rescued U-Boat men, or shot down Luftwaffe pilots,” he replies. “In December 1940, a German battleship, called Scharnhorst was sunk off Norway, with a crew of 2,000 men, most of whom perished. About 40 survived and what they told their cellmates was useful information for the Admiralty and Allied radio stations, where staff worked on compromising the morale of German troops.

Another highlight was eavesdropping on a stream of captured army officers after D-Day. It is now known that information overheard by secret listeners gave the Allies early warning of V1 and V2 rockets.

Bound by the Officials Secrets Act, secret listeners were forbidden to discuss what they had overheard with anyone, even husbands and wives.

Luckily for Lustig, his future wife, Susan, worked in the same unit, so he didn’t have to keep secrets from her. “She examined the documents of prisoners, translated them if appropriate and wrote reports about them,” he explains.

Lustig’s career in clandestine operations continued even after the Second World War ended.

In 1945, he was posted to Bad Nenndorf, near Hanover, to spy on political prisoners and industrialists, many of whom were neo-Nazis.

Today, only one of the three listening stations that housed the secret listeners – Trent Park – still stands and a campaign is now under way to save the historic venue from a planned housing development.

Lustig is currently working with Dr Fry and Enfield councillor Jason Charalambous to create a museum dedicated to “Cockfosters”, the codename given to Trent Park during the war.

It is a campaign that has been gaining momentum and one that Lustig says he hopes fervently will come to fruition. “We need the museum to preserve the memory of what happened there for future generations,” he says.

• For more information about the campaign to save Trent Park, visit www.trentparkmuseum.org.uk

• The M Room: Secret Listeners Who Bugged The Nazis, by Dr Helen Fry, is published by CreateSpace at £13.50.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Brigit Grant

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)