Second generation survivor: ‘I had visions haunting me for days’

Alex Galbinski speaks to Avital Baruch about the Holocaust in Romania, detailed in her new memoir, Frozen Mud and Red Ribbons

It took Avital Baruch until she was in her twenties to realise she had grown up in the shadow of her mother’s anxieties, brought about by her horrific experiences in the Holocaust.

Another 30 years would pass before Israeli-born Baruch realised just how much being a second generation child of Holocaust survivors had impacted on her life.

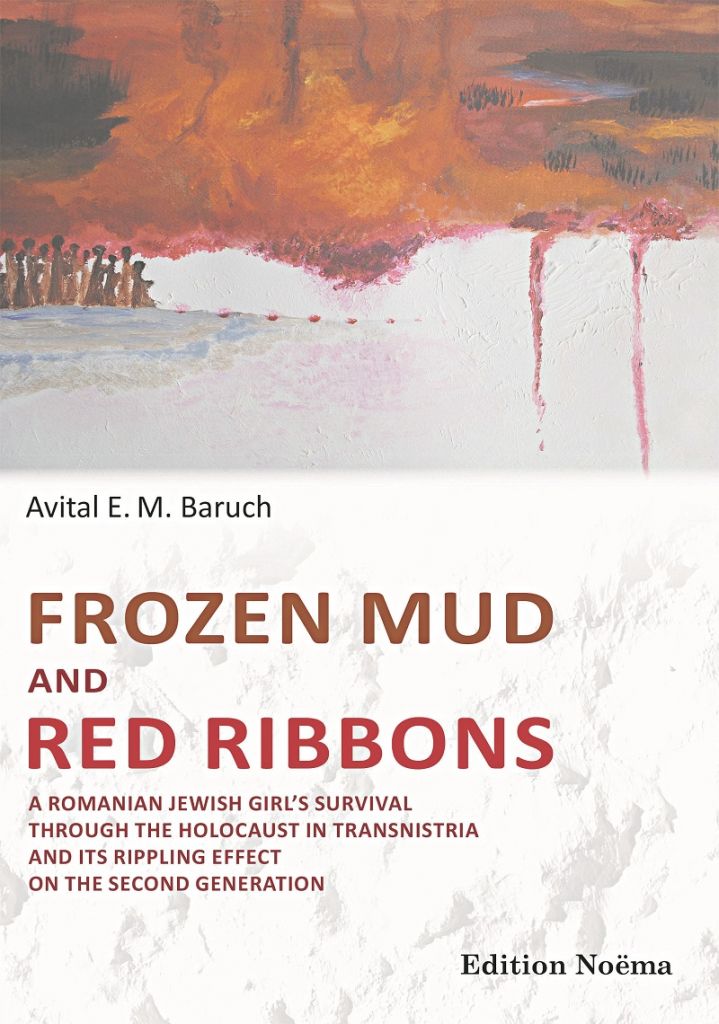

Her own journey of self-discovery, as well as the wartime experiences of her mother, Sophica, and father, Herman, is laid bare in Baruch’s recently-published memoir, Frozen Mud and Red Ribbons.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

“There were issues to do with my mother that have always bothered me, and I waited for the right time to research them,” Baruch says, explaining why she embarked on the six-year project to research her family history. “There were too many question marks in my mind, both about the family and the fate of Romanian Jews.”

In narrative form and with lively descriptions of Jewish-Romanian culture and traditions, Frozen Mud and Red Ribbons traces the family’s journey from the good – if fairly humble – times to the most horrific, incomprehensible evil, and onwards to an exciting future in Israel.

Sophica’s recollections are interspersed with those of Herman, who, having grown up in Botoșani, a city in north-eastern Romania, escaped the deportations. Their daughter’s memory of her childhood plays alongside these, casting a light on her own trauma as a member of the Second Generation.

Romania was not occupied by Nazi Germany, but allied with it and, as Baruch details in the book, about 156,000 Jews were exiled from Romania to Transnistria, where half perished.

As she writes: “They were shot, burnt alive, drowned, they contracted typhus, they starved and they became exhausted mentally and physically. But half survived it, and Sophica knew she is one of them, she knew that she is strong.”

Like many other victims of Nazi terror, Baruch’s mother was extremely reluctant to speak about her experiences, but gradually started opening up.

Baruch’s original aim was to write down her family’s story for her children. “Soon I was propelled by an inner desire to know more and to understand the full picture,” she explains.

“I felt very strongly that knowing more about my mother’s, and even my grandmother’s, generation would help me understand the way I was brought up.”

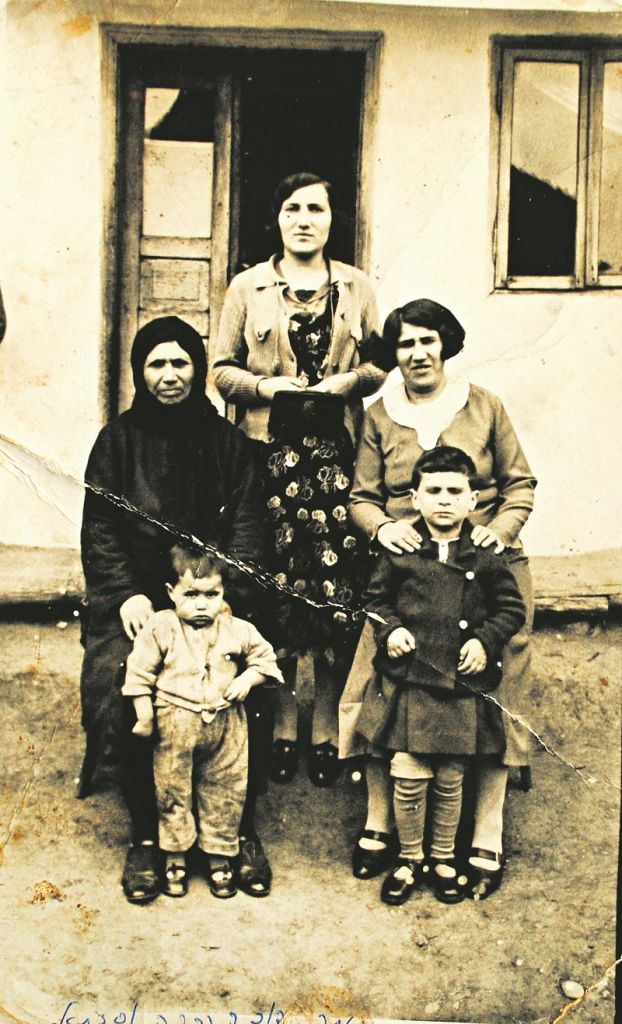

Sophica was born in 1935 in Iași, where her father was later killed in a pogrom, together with about 14,000 people. Sophica didn’t see her father from the age of two, when she moved with her mother and sister to Mihaileni, a small town on the border between Bessarabia and Bukovina.

Living in poverty after the death of her grandfather, six-year-old Sophica was excited to follow her older sister, Tonie, and start school. But her dream was cut short when, in June 1941, Mihaileni’s Jews were deported. Three years later, half of them were dead.

Baruch lays bare the horrific experiences her family endured: “Chaya, Rivka and Esther [Sophica’s aunts] carried their packages on their backs… moving with them there were gendarmes on horses, with whips in hand… every now and then they hit one of the slow walkers, including Chaya.

“Sophica, who was running ahead, turned back every so often and pulled her by the hand. But Sophica was only six and her mother 32, so the pulling wasn’t so effective.”

She details how they were forced to sleep on icy fields and walk for days at a time, eventually reaching Transnistria – which was annexed to Romania from Ukraine in 1941 – and the horrors of the labour camps there.

Tragically, Sophica’s sister, Tonie, contracted typhus – along with countless others – and was buried in a mass grave. She was just 10 when Sophica lay beside her and couldn’t understand why Tonie did not open her eyes any more.

Upon finding work in the village of Capusterna, in 1943, Chaya considered herself ‘lucky’ – and Sophica helped out, too, making bricks out of cow dung and straw.

While Baruch, 59, maintains that she is not a historian, she did conduct detailed research, interviewing people, visiting museums and reading books and testimonies. But her research also impacted on her.

“At the start of interviewing, and especially while reading other testimonies of survivors from Transnistria, I had visions haunting me for days,” she says, but adds that her father’s story contributed “playfulness, happiness, light and humour, and especially hope”.

The Romanian Holocaust is not as well-known as that of other countries, something Baruch suggests can partly be explained by Romania becoming communist after the war.

“There was not much chance to receive any reparations from Romanian authorities for atrocities during the war,” explains Baruch, a former chartered accountant turned teacher, who now lives in London.

“Unlike in Germany after the war, there was no access for western researchers to documents and proof of the events that took place and for evidence of [Romania’s wartime ruler] Antonescu’s crimes. It was only in 2004 that the Romanian government admitted its active involvement in the killing of more than 405,000 Jews [including 135,000 Transylvanian Jews taken to Auschwitz]. “Overall, the majority of Romanian survivors opted to keep their

stories quiet, bury it in the past, and work to build the country and their new families.”

Baruch’s story, while detailing unimaginable horrors, is also one of hope. Her parents met in Israel after the war, married and had Baruch, and her younger brother, Uri.

“My parents both found their move to Israel one of hope and the beginning of a new life,” she says. “They were very proud to be part of the building of the new state.”

Frozen Mud and Red Ribbons: A Romanian Jewish Girl’s Survival Through the Holocaust in Transnistria and its Rippling Effect on the Second Generation by Avital E M Baruch is priced £15. Available now.

Thank you for helping to make Jewish News the leading source of news and opinion for the UK Jewish community. Today we're asking for your invaluable help to continue putting our community first in everything we do.

For as little as £5 a month you can help sustain the vital work we do in celebrating and standing up for Jewish life in Britain.

Jewish News holds our community together and keeps us connected. Like a synagogue, it’s where people turn to feel part of something bigger. It also proudly shows the rest of Britain the vibrancy and rich culture of modern Jewish life.

You can make a quick and easy one-off or monthly contribution of £5, £10, £20 or any other sum you’re comfortable with.

100% of your donation will help us continue celebrating our community, in all its dynamic diversity...

Engaging

Being a community platform means so much more than producing a newspaper and website. One of our proudest roles is media partnering with our invaluable charities to amplify the outstanding work they do to help us all.

Celebrating

There’s no shortage of oys in the world but Jewish News takes every opportunity to celebrate the joys too, through projects like Night of Heroes, 40 Under 40 and other compelling countdowns that make the community kvell with pride.

Pioneering

In the first collaboration between media outlets from different faiths, Jewish News worked with British Muslim TV and Church Times to produce a list of young activists leading the way on interfaith understanding.

Campaigning

Royal Mail issued a stamp honouring Holocaust hero Sir Nicholas Winton after a Jewish News campaign attracted more than 100,000 backers. Jewish Newsalso produces special editions of the paper highlighting pressing issues including mental health and Holocaust remembrance.

Easy access

In an age when news is readily accessible, Jewish News provides high-quality content free online and offline, removing any financial barriers to connecting people.

Voice of our community to wider society

The Jewish News team regularly appears on TV, radio and on the pages of the national press to comment on stories about the Jewish community. Easy access to the paper on the streets of London also means Jewish News provides an invaluable window into the community for the country at large.

We hope you agree all this is worth preserving.

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)

-

By Laurent Vaughan - Senior Associate (Bishop & Sewell Solicitors)